WORKSHOP

- How to re-shaft a pre-1935 steel shafted wood

- How to re-pin an iron

- How to straighten a warped shaft

- How to finish a new hickory shaft

- How to re-grip a club

(information provided by Qld AGHS member Ross Haslam)

1. How to re-shaft a pre-1935 steel shafted wood

Once you have your pre-1935 wood the first step, and usually the most difficult in the entire process, is to carefully remove the steel shaft without causing too much damage to the wood head.

The steel shaft of most pre-1935 steel shafted clubs was held in with 2 screws. The first is usually a longer screw, approx 30mm long, runs perpendicular to the hosel of the club passing through the shaft and securing it into the clubhead. The second is a shorter screw approx 15mm long that skews back into the clubhead through the shaft where it penetrates out of the base of the club. On occasion you may find this screw is actually a pin that has been nailed through the shaft (these are difficult to get out). The other variation you may see, particularly in latter clubs, is that the screw through the hosel may have a very small head (making it very hard to extract) or may not have been used at all.

Removing screws that have been in place for 80+ years can be a trying experience. They are nearly always slotted screws that are filled with dirt and other gunk and are often worn away leaving little slot for a screwdriver to fit into. A pair of loupes is essential for examining the condition of the slot and determining the angle that it is screwed into the club. I use a Stanley knife blade to clean the slot as thoroughly as possible and make sure that I have a screwdriver that fits the slot snuggly. You need to ensure the shaft of the screwdriver runs parallel with the angle that the screw has been inserted into the club and that pressure is exerted directly down the shaft, you only get one go to get these screws out. If not the blade can twist out of the slot and damage it to a point where you will be unable to apply any pressure to remove the screw.

If they refuse to budge (and they often do) I drill them out from the base with a bit that just fits into the hollow centre of the shaft. After drilling up through the shaft the head of the hosel screw usually sticks up enough to grab with a pair of pincers or fine pliers. Remember that the end of both screws will both need to be punched into the clubhead to clear the inner wall of the steel shaft. Once they have been punched clear the shaft should turn freely and can be pulled out. If the shaft doesn’t turn freely chances are one or both of the screws will not have been punched clear of the shaft.

On rare occasions you may stumble across a club that has been previously re-shafted with a new steel shaft. These shafts are virtually impossible to remove and difficult to identify. The only real indicator is the age of the shaft compared to the head. Most of the clubs I retro fit are pre-1935 when pyratone was very much the norm for wood shafts. A shiny steel "True Temper" or similar shaft may be a give away for those clubs that have been updated during the 40's or 50's with a new steel shaft. These "newer" steel shafts are usually glued in place and are not worth the effort in trying to remove.

The remaining clubhead can now be trimmed and bored out ready for fitting of the new hickory shaft. I cut the hosel at the point where the width of the hosel will match the diameter of the new hickory shaft. Because the hosel of a steel shafted wood is narrower where it meets the steel shaft you will need to cut the hosel closer to the clubhead than you would for a normal hickory shafted club. This in turn means that the whipping will run closer to the top of the clubhead than a normal hickory shafted club.

I bore out the hosel using a step-drill that steps from 4mm to 12mm in 9 graduations. I use the “CraftRight” brand from Bunnings which come in a set of 3. There are more expensive single bits that have 12 graduations but I find the Bunnings bits are fine. I have lengthened my bit by adding a hex bit from a socket set. This allows me to drill through the hosel with plenty of clearance. I drill the hosel by hand using a cordless drill with the clubhead secured in a vice. I generally drill through the base until the 4-6mm graduation appears, from my experience this gives a hole in the base of a similar size to what is normally seen in hickory clubs. With the hole from the steel shaft already running through to the base of the club it is just a matter of using this as a guide and slowly advancing the step bit. You may shave a bit off the base plate, depending where the steel shaft exited the base, but being aluminium or brass the step bit handles this easily and will leave a neat oval shape (see the Kro-Flite above).

Fitting the new hickory shaft is now simply a matter of carefully filing down the end of the shaft until it is a reasonably snug fit into the new bored-out hosel. I have a selection of files and rasps that I use for this. Once I’m happy with the fit I set it in place with “Ultra Clear” Araldite (you can use whatever glue you prefer). The important thing at this point is to ensure the grain of the shaft runs perpendicular to the face of the club. I mark the grain on the butt end of all my shafts so that aligning the shaft is no problem.

Now that the shaft is set into place all that remains is the finishing of the club. To ensure a seamless transition where the hosel and shaft meet I use epoxy putty carefully sanded back. It is a time consuming process but if done well the taper from clubhead to shaft is as indistinguishable as it is in all hickory shafted woods. The nice thing about epoxy putty is that it will take stain so you can colour it to match the club head or shaft if you desire.

The screw hole at the back of the hosel can sometimes be the only giveaway that a once steel shafted wood has been re-shafted with a hickory shaft. After experimenting with casting resin to repair a damaged face insert I decided that resin would be the ideal material to fill the hole left by the hosel screw. I place the club in the vice making sure the hosel area is level. The casting resin I use takes 5-10 mins to set so when ready I line the hole with 5 min araldite and then carefully syringe in the resin to just overfill the hole. When set it can be filed or sanded down to the desired finish. I have begun stamping my resin plugs with the letter that represents the wood, so “B” for Brassie and so on. If the club has an insert face I try to match the plug colour to the colour of the insert.

My 1935 Wilson "Walter Hagen Tom-Boy" re-shafted spoon

My 1935 Wilson "Walter Hagen Tom-Boy" re-shafted spoon

2. How to re-pin an Iron

I usually re-pin all of the clubs I am going to use for play. An original club that may seem tight in the hosel at first may loosen up after a few hits and will then spend the rest of the round in the bag unusable. It's a simple procedure that ensures your club is ready for play.

The first step is usually removing the pin from a loose iron. At times they can be extremely difficult to find but rest assured there is one there somewhere, the epoxies that we rely on in modern club fitting were not available during the hickory era. If the hosel is rusted over I clean them up with a bit of sandpaper, this often reveals the location of the pin. A pair of loupes or a magnifying glass are handy to have around. You're looking for a small circle (approx 3mm in diameter) that will be 15-25mm from the end of the hosel. The pin position should be perpendicular to the blade so that when the blade is laying flat on the bench the pin is facing skywards. If both the blade and estimated pin position are both in the same plane then chances are you haven't found the pin. Once you have found it mark it with a permanent marker and check and re-check that you are happy with its location.

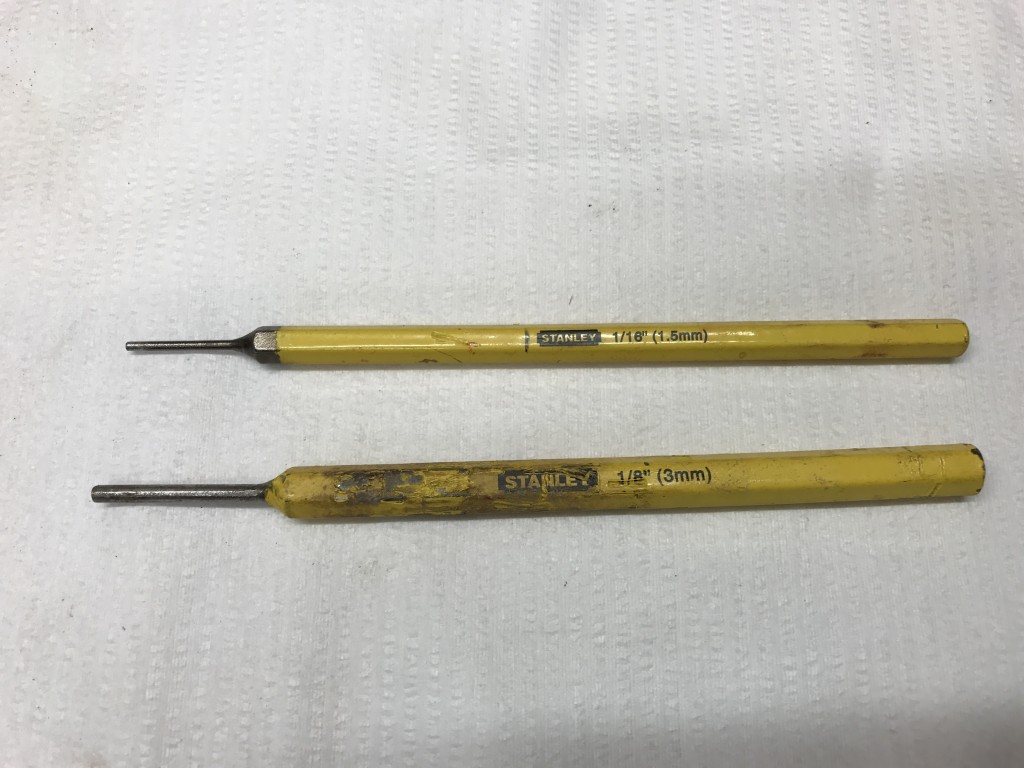

If you are mistaken don't panic, you won't be the first or last person to mistakenly punch a nice circular dent in the hosel of a club, sometimes the pin positions are so well hidden that you will have to hit and hope. The good news is that the impact of the punch will often reveal the true location of the pin. Clamp the club so that the hosel, and not the shaft, will take the force of the blow from the hammer when you're punching the pin out. I use a 3mm and 1.5mm punch to remove the pin. I start with the 3mm punch. If the pin is tight and doesn't come out easily I finish punching with the smaller 1.5mm punch so that I don't risk damaging the hosel on the far side.

With the pin removed a lose head will often fall from the shaft. At times the head will need gentle persuasion and sometimes you will come across a head that is so firmly attached that you will wonder why you're re-pinning it in the first place. If the head doesn't come away easily a few taps around the hosel with a RUBBER mallet may be enough to break the seal and loosen it so that you can twist it off. Heating the club head with a heat gun for a few minutes will also help to loosen it. On occasion I will use the rubber mallet to dislodge a stubborn head. A sharp blow to the top of the blade, being careful to hit directly down parallel to the hosel will usually do the trick on even the most stubborn of heads. If the shaft is being re-used be very careful not to damage it with your enthusiasm to remove the head. It may take several attempts of heating and gentle tapping of the hosel before it loosens, patience is paramount here. If the shaft is damaged and not for re-use then you can be more aggressive with your removal strategy but be aware that getting the hosel section of the shaft out of a club after you've broken the shaft off requires extra work that you should be able to avoid.

If I can't get the head off and the shaft is for play then I simple re-pin as is and assume the fit is as good as it needs to be. This is not uncommon and makes the re-pinning task much easier. If the head does eventually loosen through play then it can be re-pinned at that stage.

I re-drill ALL of my pin holes with a 3.5mm cobalt drill. I use the cobalt bits because they retain their edge longer especially when drilling through stainless steel heads, which are not uncommon. I use 3.5mm brass rod for ALL of my pins. I use this combination for several reasons:

- It ensures the hole and pin are an exact match

- The brass rods are easy to source from hobby shops and are relatively inexpensive (they are also available in non-metric sizes)

- The brass rod is easy to cut into short lengths (I use a pair of good quality pincers)

- The brass pin will always be easy to find for future maintenance.

- The brass is easy to file down

If I am re-pinning the original shaft I re-drill the hosel with the shaft in place so that the new hole aligns exactly through the hosel and shaft. When I'm using a new shaft I follow the same procedure except there is obviously no old pin hole in the shaft to guide the drill bit. Take great care when drilling the 3.5mm pin hole in a new shaft. Drill 1/2 way from both sides that way even if the hole doesn't align exactly in the middle of the shaft the difference will be filled with epoxy when you glue the pin in place. I then clean out the hosel and remove any built up "gunk" on the (old) shaft taper. I mark the correct alignment of the shaft with a small black dot on the hosel and on the hosel end of the shaft so that I know the correct orientation of the shaft in the club head. When you are gluing the shaft in place it can be difficult to align the club correctly with glue oozing out of the pin holes. To avoid mishaps I prefer a two step process, glue the head first and when dry insert and glue the pin.

I run a 3.2mm welding rod through the pin hole while the epoxy dries. REMEMBER to turn the rod several times while the glue starts to take and remove after 2-3 mins before the glue sets.

When the head is firmly glued in place I carefully run the 3.5mm drill back through the pin hole to remove any glue that has built up. DON'T FORGET TO DO THIS! Apply epoxy in the hole and carefully insert the brass pin making sure it protrudes beyond the hosel on both sides. The beauty of using pincers to cut the brass rod is that it leaves the ends pointed which makes it easier to get it started in the pin hole. The pin should tap through the hosel with a little resistance. If it is difficult to get through then you've probably forgotten to re-drill the hole after setting the head. Don't try and force it, pull the pin out and make sure the hole is re-drilled before progressing. When set I file and sand so that it is flush on both sides.

I always use rubber gloves when using epoxy and have plenty of rags available to wipe up excess glue.

3. How to straighten a warped shaft

You will need a heat gun, a pair of leather gloves and a good enough eye to sight along the shaft. The other piece of equipment I use is handy for many club related jobs and is especially handy when I need to straighten a bowed shaft. A piece of 150-200mm x 40-50mm pine approximately 750mm long with a 10-12mm channel cut out of the narrow edge. I will call it my "shaft holder thingy".

The channel in the edge of the holder allows the club to be orientated in any plane and lightly clamped in place to prevent it from moving. For correcting bends the straight edge of the timber will highlight the bowing in the shaft. I prefer to straighten shafts with the head and grips removed. Fortunately most of the clubs I have that need attention in this area are prepared that way. With the club laying in the groove, bowed side facing up, I run my heat gun back and forth steadily along the length of the entire shaft for 3-4 minutes being careful not to burn or darken the shaft. With the club in the groove of the holder and leather gloves on I use my left hand (I am right handed) to push down firmly, moving along through the bowed section while at the same time pulling up on the butt of the shaft with my right hand. Having the shaft fixed against the timber allows me to control the amount of leverage I apply and to what section of the shaft I apply it to. For example, if the last 300-400mm of the butt section of the shaft is bowed I can start applying pressure directly to that area with my left hand whilst pulling up with my right hand. The remainder of the shaft remains fixed against the straight edge and is not affected by the force being applied to the opposite end.

I have tried several different straightening methods and this is the technique that I find gives me the greatest control and best results. It can take a bit of practice but after you have straightened a few shafts you will get a "feel" for the amount of tension a club needs and will tolerate without risking damage. A hot shaft is very malleable and will bend and straighten quite readily. I have had the shaft of a wooden cleek heated to a point where I could rotate the head of the club 180 degrees with no damage to the shaft whatsoever (it remains in my bag today with the original shaft still in place working like a charm). If the shaft has multiple bends I correct the worst first, allow the club to cool and then address the next. Don't expect to be able to straighten every shaft perfectly, some have a mind of their own and you will have to be satisfied with the best you can do. This is one area of club repair that requires a certain amount of feel and one that you will get better at the more you do.

4. How to finish a new hickory shaft

These steps assume you have already glued the shaft in place and are now ready to trim and finish the new hickory shaft.

Depending on the amount of “play” or “flex” you like in your clubs the finishing of the shaft is relatively straight forward. Usually if you prefer a stiff shaft then the new shaft you have installed should have been rated stiff so not much finishing will be required. If you’ve used a shaft rated as “regular” and you want a stiff feeling shaft then you’ve probably just wasted a new shaft. This “feel”can also be influenced by the weight of the clubhead. For example, a heavy wood head (one from a steel shafted club for example) will generally need a stiffer heavier shaft and vice versa. Remember that the weights of the heads from this era can vary significantly which will obviously affect the feel and performance of the hickory shaft.

The modern manufacturers of hickory clubs, such as Tad Moore, follow an extensive grading and testing process, which includes deflection and frequency boards, to evaluate the shafts finished flex.

The sanding process that I go through is to tweak those shafts to my individual preference. As I prefer a slightly “whippier” shaft, all of my clubs with new shafts have been adjusted to suit. To do this I “road test” my clubs as I am tweaking them. In my opinion this is the best way to tailor a club to meet your personal needs.

Remember, Hickory is a natural material that can have significant variation in its mechanical characteristics. Add to that equation iron and wood heads of varying weights and designs and it’s not hard to see why the performance of individual period clubs needs to be assessed and adjusted where needed.

One of the biggest arguments for the use of modern hickory clubs is the uniformity amongst sets. The weights and designs of modern hickory club heads are made to specific, well researched criteria which helps to eliminate some the variability in performance that we often see with original clubs.

Tools/equipment you will need

- Good selection of sandpaper. 40, 80, 120, 180, 240, 400 is the grit range I use when preparing a shaft

- Heavy bastard file. I use one of these when I need to take a “bit” off the shaft

- Bench and vice

- Masking tape

- Spray can of semi-gloss polyurethane. (I use the Mincare Spar range of polyurethanes).

- A ‘Shaft Holder thingy” (see “shaft straightening” article) comes in handy for resting shaft across when sanding or staining etc.

- "Feast and Watson Prooftint" wood stain. I use a mixture of 3 colours to get the aged hickory look.

Golden teak : Teak Brown : Elm

2 parts : 2 parts : 1 part

If the shaft is already attached to the head you will need to mask the head to prevent any overspray from the shaft getting on the head and just as a precaution against accidental damage. I use a cloth and masking tape.

The new shafts that I use are finished to a pre-determined taper ready for hickory play. As such, when I am preparing a shaft I am careful to sand (remove timber) along the entire length of the shaft at a constant rate to maintain the pre-set taper, from just above the epoxy join (on a re-shafted wood) to at least the beginning of the grip section of the shaft. For new iron shafts I begin sanding where the shaft flairs to join the hosel. If you prefer a thicker grip then there is no need to sand beyond where the grip would finish. If you prefer a thinner grip then sand all the way to the end of the shaft.

Begin with the 40 grit and work your way down. Remember timber will be removed from the shaft with every pass. As the sandpaper becomes finer less timber will be taken away but it will still reduce the stiffness of the shaft so make sure you allow for that and stop sanding with the coarser papers before you reach what you think is the ideal flex. I do all of my sanding by hand, carefully rotating the shaft as I sand to ensure the round profile and taper of the shaft is maintained. It’s a slow process but one that allows me to control precisely what I am doing.

REMEMBER YOU CAN ALWAYS TAKE MORE TIMBER OFF BUT YOU CAN NEVER PUT IT BACK ON!

Once I have finished sanding the shaft I move on to staining and finishing. I follow the same method I describe below for staining and finishing all of my original shafts as well. With original shafts I apply a coat of paint stripper (to remove any old finishes) wiped off with fine grade steel wool. I then wipe the shaft over with a damp cloth and, after it is dry, finish with a light sand with 400 grit sand paper.

I make up my mixture in a 50ml container according to the ratio described above.

I apply the stain generously with a brush making sure it penetrates the grain of the timber. To prevent runs I rotate the shaft continuously as it dries. The heavy coat of stain leaves the shaft dark in appearance. When nearly dry I use a soft cloth wet with the stain to lightly rub over the shaft to even out any runs or overly dark areas, be careful not to rub to hard or you will remove too much the stain already applied. I finish the shaft with 2-3 coats of the spray semi-gloss polyurethane which lightens the colour back to what I think gives the shaft a nice aged patina. If you don't like the extra sheen of the semi-gloss then go with a satin polyurethane.

Polyurethane offers the best level of protection and durability for a timber finish and is both readily available and easy to apply. Remember whatever finish you use on the shaft it is ONLY there to act as a level of protection to the exterior of the shaft. You can't "condition" a shaft or make it more supple by applying one type of finish compared to another. Read more about this in my "hickory shaft facts" in the CLUBS section.